One Unique Feature of Hellenistic Art Was for a Sculptor to Carve Drapery and Folds in Clothing

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the principal surviving type of fine ancient Greek art equally, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies iii major stages in awe-inspiring sculpture in bronze and rock: the Archaic (from about 650 to 480 BC), Classical (480–323) and Hellenistic. At all periods in that location were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

The Greeks decided very early on that the homo course was the well-nigh of import subject for artistic endeavour.[1] Seeing their gods equally having human class, at that place was little stardom between the sacred and the secular in art—the human body was both secular and sacred. A male person nude of Apollo or Heracles had only slight differences in treatment to one of that year's Olympic boxing champion. The statue, originally single simply past the Hellenistic menstruum often in groups was the ascendant form, though reliefs, often so "loftier" that they were almost gratuitous-standing, were also of import.

Materials [edit]

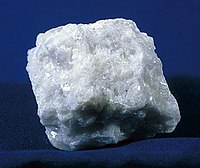

By the classical menses, roughly the fifth and quaternary centuries, awe-inspiring sculpture was composed almost entirely of marble or statuary; with cast bronze becoming the favoured medium for major works by the early on 5th century; many pieces of sculpture known merely in marble copies made for the Roman market were originally made in bronze. Smaller works were in a bully multifariousness of materials, many of them precious, with a very large production of terracotta figurines. The territories of ancient Greece, except for Sicily and southern Italy, contained abundant supplies of fine marble, with Pentelic and Parian marble the about highly prized. The ores for bronze were also relatively easy to obtain.[ii]

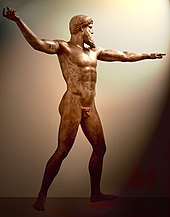

Both marble and statuary are easy to form and very durable; as in most ancient cultures at that place were no doubt likewise traditions of sculpture in forest about which we know very picayune, other than acrolithic sculptures, usually large, with the head and exposed flesh parts in marble just the clothed parts in wood. As bronze e'er had a significant scrap value very few original bronzes have survived, though in recent years marine archaeology or trawling has added a few spectacular finds, such every bit the Artemision Statuary and Riace bronzes, which have significantly extended modern agreement. Many copies of the Roman flow are marble versions of works originally in bronze. Ordinary limestone was used in the Archaic menstruum, but thereafter, except in areas of modern Italia with no local marble, but for architectural sculpture and decoration. Plaster or stucco was sometimes used for the hair only.[3]

Chryselephantine sculptures, used for temple cult images and luxury works, used gold, most often in leaf grade and ivory for all or parts (faces and hands) of the effigy, and probably gems and other materials, but were much less common, and but fragments have survived. Many statues were given jewellery, equally can be seen from the holes for attaching information technology, and held weapons or other objects in different materials.[4]

Painting of sculpture [edit]

Despite appearing white today, Greek sculptures were originally painted.[five] [half-dozen] [7] This color restoration shows what a statue of a Trojan archer from the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina would have originally looked like.[vi]

Ancient Greek sculptures were originally painted bright colors;[5] [6] [7] they merely appear white today considering the original pigments accept deteriorated.[5] [6] References to painted sculptures are found throughout classical literature,[v] [half dozen] including in Euripides's Helen in which the eponymous grapheme laments, "If only I could shed my beauty and presume an uglier aspect/The way y'all would wipe colour off a statue."[6] Some well-preserved statues all the same comport traces of their original coloration[5] and archaeologists can reconstruct what they would have originally looked like.[5] [6] [7]

Development of Greek sculptures [edit]

Geometric [edit]

Information technology is commonly thought that the earliest incarnation of Greek sculpture was in the form of wooden or ivory cult statues, outset described past Pausanias as xoana.[8] No such statues survive, and the descriptions of them are vague, despite the fact that they were probably objects of veneration for hundreds of years. The first piece of Greek statuary to be reassembled since is probably the Lefkandi Centaur, a terracotta sculpture found on the island of Euboea, dated c. 920 BC. The statue was constructed in parts, before being dismembered and buried in ii dissever graves. The centaur has an intentional mark on its human knee, which has led researchers to postulate[ix] that the statue might portray Cheiron, presumably kneeling wounded from Herakles' arrow. If then, it would exist the primeval known depiction of myth in the history of Greek sculpture.

The forms from the Geometric period (c. 900 to 700 BC) were importantly terracotta figurines, bronzes, and ivories. The bronzes are chiefly tripod cauldrons, and freestanding figures or groups. Such bronzes were made using the lost-wax technique probably introduced from Syrian arab republic, and are almost entirely votive offerings left at the Hellenistic civilization Panhellenic sanctuaries of Olympia, Delos, and Delphi, though these were likely manufactured elsewhere, equally a number of local styles may be identified by finds from Athens, Argos, and Sparta. Typical works of the era include the Karditsa warrior (Athens Br. 12831) and the many examples of the equestrian statuette (for example, NY Met. 21.88.24 online). The repertory of this bronze work is not bars to continuing men and horses, nonetheless, equally vase paintings of the time also depict imagery of stags, birds, beetles, hares, griffins and lions. There are no inscriptions on early-to-middle geometric sculpture, until the appearance of the Mantiklos "Apollo" (Boston 03.997) of the early on 7th century BC constitute in Thebes. The figure is that of a standing man with a pseudo-daedalic form, underneath which lies the hexameter inscription reading "Mantiklos offered me as a tithe to Apollo of the silver bow; do you, Phoibos [Apollo], give some pleasing favour in return".[10] Apart from the novelty of recording its own purpose, this sculpture adapts the formulae of oriental bronzes, as seen in the shorter more triangular face and slightly advancing left leg. This is sometimes seen as anticipating the greater expressive liberty of the 7th century BC and, equally such, the Mantiklos effigy is referred to in some quarters as proto-Daedalic.

Primitive [edit]

The Sabouroff head, an important instance of Tardily Archaic Greek marble sculpture, and a precursor of true portraiture, ca. 550-525 BCE.[11]

Inspired by the monumental rock sculpture of ancient Arab republic of egypt[12] and Mesopotamia, the Greeks began again to carve in stone. Complimentary-standing figures share the solidity and frontal stance characteristic of Eastern models, simply their forms are more dynamic than those of Egyptian sculpture, as for example the Lady of Auxerre and Trunk of Hera (Early Primitive period, c. 660–580 BC, both in the Louvre, Paris). After about 575 BC, figures such as these, both male and female person, began wearing the and so-chosen archaic smiling. This expression, which has no specific appropriateness to the person or situation depicted, may take been a device to give the figures a distinctive human being characteristic.

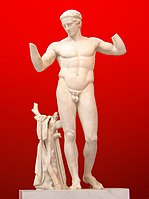

Three types of figures prevailed—the standing nude male youth (kouros, plural kouroi), the standing draped girl (kore, plural korai), and the seated adult female. All emphasize and generalize the essential features of the human effigy and prove an increasingly accurate comprehension of man anatomy. The youths were either sepulchral or votive statues. Examples are Apollo (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), an early piece of work; the Strangford Apollo from Anafi (British Museum), a much later work; and the Anavyssos Kouros (National Archaeological Museum of Athens). More of the musculature and skeletal structure is visible in this statue than in earlier works. The standing, draped girls accept a wide range of expression, as in the sculptures in the Acropolis Museum of Athens. Their drapery is carved and painted with the delicacy and meticulousness common in the details of sculpture of this menstruation.

The Greeks thus decided very early on on that the human form was the well-nigh of import bailiwick for artistic try. Seeing their gods equally having human form, at that place was no stardom between the sacred and the secular in fine art—the man torso was both secular and sacred. A male nude without any attachments such as a bow or a lodge, could just equally easily be Apollo or Heracles every bit that year's Olympic boxing champion. In the Primitive Period the most important sculptural class was the kouros (Encounter for case Biton and Kleobis). The kore was also common; Greek art did not nowadays female nudity (unless the intention was pornographic) until the 4th century BC, although the development of techniques to represent drapery is obviously important.

As with pottery, the Greeks did not produce sculpture just for artistic brandish. Statues were commissioned either past aristocratic individuals or by the state, and used for public memorials, as offerings to temples, oracles and sanctuaries (as is frequently shown by inscriptions on the statues), or equally markers for graves. Statues in the Primitive period were not all intended to represent specific individuals. They were depictions of an ideal—beauty, piety, honor or cede. These were always depictions of young men, ranging in historic period from adolescence to early maturity, even when placed on the graves of (presumably) elderly citizens. Kouroi were all stylistically like. Graduations in the social stature of the person commissioning the statue were indicated by size rather than creative innovations.

-

Dipylon Kouros, c. 600 BC, Athens, Kerameikos Museum.

-

-

-

Classical [edit]

The Classical period saw a revolution of Greek sculpture, sometimes associated by historians with the popular civilisation surrounding the introduction of democracy and the finish of the aristocratic culture associated with the kouroi. The Classical period saw changes in the style and function of sculpture, forth with a dramatic increase in the technical skill of Greek sculptors in depicting realistic human forms. Poses also became more naturalistic, notably during the kickoff of the menstruation. This is embodied in works such equally the Kritios Boy (480 BC), sculpted with the earliest known employ of contrapposto ('counterpose'), and the Charioteer of Delphi (474 BC), which demonstrates a transition to more naturalistic sculpture. From about 500 BC, Greek statues began increasingly to draw real people, as opposed to vague interpretations of myth or entirely fictional votive statues, although the style in which they were represented had not still developed into a realistic form of portraiture. The statues of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, fix upward in Athens mark the overthrow of the aloof tyranny, and take been said to exist the first public monuments to show actual individuals.

The Classical Catamenia besides saw an increase in the utilize of statues and sculptures equally decorations of buildings. The characteristic temples of the Classical era, such as the Parthenon in Athens, and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, used relief sculpture for decorative friezes, and sculpture in the round to make full the triangular fields of the pediments. The hard artful and technical challenge stimulated much in the way of sculptural innovation. Nigh of these works survive only in fragments, for example the Parthenon Marbles, roughly half of which are in the British Museum.

Funeral statuary evolved during this period from the rigid and impersonal kouros of the Archaic menstruation to the highly personal family groups of the Classical period. These monuments are commonly found in the suburbs of Athens, which in ancient times were cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. Although some of them depict "ideal" types—the mourning mother, the dutiful son—they increasingly depicted real people, typically showing the departed taking his dignified go out from his family. This is a notable increase in the level of emotion relative to the Primitive and Geometrical eras.

Another notable change is the burgeoning of creative credit in sculpture. The entirety of information known about sculpture in the Primitive and Geometrical periods are centered upon the works themselves, and seldom, if ever, on the sculptors. Examples include Phidias, known to have overseen the design and building of the Parthenon, and Praxiteles, whose nude female sculptures were the first to be considered artistically respectable. Praxiteles' Aphrodite of Knidos, which survives in copies, was often referenced to and praised by Pliny the Elder.

Lysistratus is said to accept been the offset to employ plaster molds taken from living people to produce lost-wax portraits, and to have also adult a technique of casting from existing statues. He came from a family unit of sculptors and his brother, Lysippos of Sicyon, produced fifteen hundred statues in his career.[13]

The Statue of Zeus at Olympia and the Statue of Athena Parthenos (both chryselephantine and executed by Phidias or under his direction, and considered to exist the greatest of the Classical Sculptures), are lost, although smaller copies (in other materials) and good descriptions of both withal exist. Their size and magnificence prompted rivals to seize them in the Byzantine period, and both were removed to Constantinople, where they were subsequently destroyed.

-

Kritios Boy. Marble, c. 480 BC. Acropolis Museum, Athens.

-

-

Family grouping on a grave marker from Athens, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

-

-

-

Hellenistic [edit]

The transition from the Classical to the Hellenistic period occurred during the 4th century BC. Greek fine art became increasingly diverse, influenced by the cultures of the peoples drawn into the Greek orbit, by the conquests of Alexander the Keen (336 to 323 BC). In the view of some art historians, this is described as a pass up in quality and originality; nevertheless, individuals of the time may not have shared this outlook. Many sculptures previously considered classical masterpieces are at present known to exist of the Hellenistic age. The technical ability of the Hellenistic sculptors are clearly in evidence in such major works as the Winged Victory of Samothrace, and the Pergamon Altar. New centres of Greek culture, particularly in sculpture, adult in Alexandria, Antioch, Pergamum, and other cities. By the 2nd century BC, the rising power of Rome had besides absorbed much of the Greek tradition—and an increasing proportion of its products equally well.

During this period, sculpture again experienced a shift towards increasing naturalism. Mutual people, women, children, animals, and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was deputed by wealthy families for the beautification of their homes and gardens. Realistic figures of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection. At the same time, new Hellenistic cities springing up in Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This made sculpture, like pottery, an industry, with the consequent standardisation and (some) lowering of quality. For these reasons, quite a few more Hellenistic statues survive to the present than those of the Classical period.

Alongside the natural shift towards naturalism, there was a shift in expression of the sculptures likewise. Sculptures began expressing more power and energy during this fourth dimension period. An easy way to see the shift in expressions during the Hellenistic period would be to compare it to the sculptures of the Classical period. The classical period had sculptures such as the Charioteer of Delphi expressing humility. The sculptures of the Hellenistic period however saw greater expressions of ability and free energy as demonstrated in the Jockey of Artemision.[16]

Some of the best known Hellenistic sculptures are the Winged Victory of Samothrace (2nd or 1st century BC), the statue of Aphrodite from the island of Melos known as the Venus de Milo (mid-2nd century BC), the Dying Gaul (nearly 230 BC), and the monumental group Laocoön and His Sons (belatedly 1st century BC). All these statues depict Classical themes, but their handling is far more than sensuous and emotional than the austere gustation of the Classical period would accept allowed or its technical skills permitted. Hellenistic sculpture was besides marked past an increase in calibration, which culminated in the Colossus of Rhodes (late third century), thought to have been roughly the same size as the Statue of Liberty. The combined effect of earthquakes and looting have destroyed this as well as any other very big works of this period that might accept existed.

Following the conquests of Alexander the Slap-up, Greek civilization spread as far as India, every bit revealed by the excavations of Ai-Khanoum in eastern Afghanistan, and the culture of the Greco-Bactrians and the Indo-Greeks. Greco-Buddhist fine art represented a syncretism betwixt Greek art and the visual expression of Buddhism. Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century surrounding the (now submerged) ancient Egyptian city of Heracleum include a 4th-century BC delineation of Isis. The depiction is unusually sensual for depictions of the Egyptian goddess, besides as being uncharacteristically detailed and feminine, marking a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms effectually the time of Alexander the Keen'southward conquest of Arab republic of egypt.

In Goa, India, were found Buddha statues in Greek styles. These are attributed to Greek converts to Buddhism, many of whom are known to have settled in Goa during Hellenistic times.[17] [18]

-

-

Ancient Greek terracotta head of a young man, found in Tarent, c. 300 BC, Antikensammlung Berlin.

-

Female head incorporating a vase (lekythos), c. 325-300 BC.

-

Bronze portrait of an unknown sitter, with inlaid eyes, Hellenistic period, 1st century BC, found in Lake Palestra of the Isle of Delos.

-

Gravestone of a adult female with her child slave attending to her, c. 100 BC (early on flow of Roman Greece)

Cult images [edit]

All ancient Greek temples and Roman temples normally contained a cult image in the cella. Access to the cella varied, merely apart from the priests, at the least some of the general worshippers could admission the cella some of the time, though sacrifices to the deity were normally made on altars outside in the temple precinct (temenos in Greek). Some cult images were easy to run across, and were what we would call major tourist attractions. The paradigm normally took the course of a statue of the deity, originally less than life-size, so typically roughly life-size, but in some cases many times life-size, in marble or statuary, or in the specially prestigious form of a Chryselephantine statue using ivory plaques for the visible parts of the body and gold for the clothes, around a wooden framework. The about famous Greek cult images were of this type, including the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, and Phidias'south Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon in Athens, both jumbo statues now completely lost. Fragments of two chryselephantine statues from Delphi have been excavated. Cult images by and large held or wore identifying attributes, which is one way of distinguishing them from the many other statues of deities in temples and other locations.

The acrolith was another blended class, this time a cost-saving ane with a wooden trunk. A xoanon was a primitive and symbolic image, usually in wood, some perhaps comparable to the Hindu lingam, although the oldest cult image from the Greek globe, the Minoan Palaikastro Kouros, is highly sophisticated. Many xoana were retained and revered for their antiquity in later periods; they were ofttimes light enough to be carried in processions. Many of the Greek statues well known from Roman marble copies were originally temple cult images, which in some cases, such as the Apollo Barberini, can exist credibly identified. A very few actual originals survive, for example the bronze Piraeus Athena (ii.35 metres high, including a helmet).

In Greek and Roman mythology, a "palladium" was an paradigm of dandy artifact on which the safe of a city was said to depend, especially the wooden one that Odysseus and Diomedes stole from the citadel of Troy and which was later taken to Rome by Aeneas. (The Roman story was related in Virgil's Aeneid and other works.)

Drapery [edit]

Female [edit]

Male [edit]

Encounter as well [edit]

- Meniskos, a device for protecting statues placed outside

Notes [edit]

- ^ Cook, 19

- ^ Cook, 74–75

- ^ Cook, 74–76

- ^ Cook, 75–76

- ^ a b c d e f Brinkmann, Vinzenz (2008). "The Polychromy of Aboriginal Greek Sculpture". In Panzanelli, Roberta; Schmidt, Eike D.; Lapatin, Kenneth (eds.). The Color of Life: Polychromy in Sculpture from Antiquity to the Nowadays. Los Angeles, California: The J. Paul Getty Museum and the Getty Research Institute. pp. 18–39. ISBN978-0-89-236-918-eight.

- ^ a b c d due east f g Gurewitsch, Matthew (July 2008). "True Colors: Archeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann insists his eye-popping reproductions of ancient Greek sculptures are correct on target". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Prisco, Jacopo (thirty November 2017). "'Gods in Color' returns antiquities to their original, colorful grandeur". CNN style. CNN. Cable News Network. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ The term xoanon and the ascriptions are both highly problematic. A.A. Donohue's Xoana and the origins of Greek sculpture, 1988, details how the term had a variety of meanings in the ancient world not necessarily to do with the cult objects

- ^ [one] Archived Feb 27, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Μαντικλος μ' ανεθεκε ϝεκαβολοι αργυροτοχσοι τας {δ}δε|κατας· τυ δε Φοιβε διδοι χαριϝετταν αμοιϝ[αν]," transliterated as "Mantiklos thousand' anetheke wekaboloi argyrotokhsoi tas dekatas; tu de Phoibe didoi khariwettan amoiw[an]"

- ^ CAHN, HERBERT A.; GERIN, DOMINIQUE (1988). "Themistocles at Magnesia". The Numismatic Chronicle. 148: 20 & Plate 3. JSTOR 42668124.

- ^ The debt of archaic Greek sculpture to Egyptian canons was recognized in Antiquity: meet Diodorus Siculus, i.98.5–nine.

- ^ Gagarin, 403

- ^ a b Hutchinson, Godfrey (2014). Sparta: Unfit for Empire. Frontline Books. p. 43. ISBN9781848322226.

- ^ "IGII2 6217 Epitaph of Dexileos, cavalryman killed in Corinthian war (394 BC)". www.atticinscriptions.com.

- ^ Stele, R. Web. 24 November 2013. <http://www.ancientgreece.com/s/Sculpture/>

- ^ Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu: commune gazetteer, Book 1. panajim Goa: Gazetteer Dept., Govt. of the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu, 1979. 1979. pp. (encounter page seventy).

- ^ (come across Pius Melkandathil,Martitime activities of Goa and the Indian sea.)

References [edit]

- Cook, R.One thousand., Greek Art, Penguin, 1986 (reprint of 1972), ISBN 0140218661

- Gagarin, Michael, Elaine Fantham (contributor), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Greece and Rome, Book 1, Oxford Academy Press, 2010, ISBN 9780195170726

- Stele, R. Spider web. 24 November 2013. http://www.ancientgreece.com/s/Sculpture/

Bibliography [edit]

- Boardman, John. Greek Sculpture: The Archaic Period: A Handbook. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

- --. Greek Sculpture: The Classical Menstruation: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

- --. Greek Sculpture: The Belatedly Classical Period and Sculpture In Colonies and Overseas. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

- Dafas, K. A., 2019. Greek Large-Calibration Bronze Bronze: The Late Archaic and Classical Periods, Constitute of Classical Studies, Schoolhouse of Avant-garde Study, Academy of London, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, Monograph, BICS Supplement 138 (London).

- Dillon, Sheila. Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects, and Styles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Furtwängler, Adolf. Masterpieces of Greek Sculpture: A Series of Essays On the History of Art. London: W. Heinemann, 1895.

- Jenkins, Ian. Greek Architecture and Its Sculpture. Cambridge: Harvard University Printing, 2006.

- Kousser, Rachel Meredith. The Afterlives of Greek Sculpture: Interaction, Transformation, and Devastation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Marvin, Miranda. The Language of the Muses: The Dialogue Betwixt Roman and Greek Sculpture. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.

- Mattusch, Carol C. Classical Bronzes: The Fine art and Craft of Greek and Roman Statuary. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996.

- Muskett, Thousand. M. Greek Sculpture. London: Bristol Classical Press, 2012.

- Neer, Richard. The Emergence of the Classical Manner In Greek Sculpture. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Neils, Jenifer. The Parthenon Frieze. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Palagia, Olga. Greek Sculpture: Part, Materials, and Techniques In the Primitive and Classical Periods. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Palagia, Olga, and J. J. Pollitt. Personal Styles In Greek Sculpture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Pollitt, J. J. The Aboriginal View of Greek Fine art: Criticism, History, and Terminology. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974.

- --. Fine art In the Hellenistic Age. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Printing, 1986.

- Ridgway, Brunilde Sismondo. The Archaic Style In Greek Sculpture. 2nd ed. Chicago: Ares, 1993.

- --. 4th-Century Styles In Greek Sculpture. Madison: Academy of Wisconsin Press, 1997.

- Smith, R. R. R. Hellenistic Imperial Portraits. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

- --. Hellenistic Sculpture: A Handbook. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

- Spivey, Nigel Jonathan. Understanding Greek Sculpture: Ancient Meanings, Modern Readings. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

- --. Greek Sculpture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Stanwick, Paul Edmund. Portraits of the Ptolemies: Greek Kings As Egyptian Pharaohs. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002.

- Stewart, Andrew F. Greek Sculpture: An Exploration. New Haven: Yale Academy Printing, 1990.

- --. Faces of Power: Alexander's Image and Hellenistic Politics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

- von Mach, Edmund. Greek Sculpture: Its Spirit and Its Principles. New York: Parkstone Press International, 2006.

- --. Greek Sculpture. New York: Parkstone International, 2012.

- Winckelmann, Johann Joachim, and Alex Potts. History of the Art of Antiquity. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2006.

External links [edit]

- Classic Greek Sculpture to Late Hellenistic Era, lecture past professor Kenney Mencher, Ohlone College

- Sideris A., Aegean Schools of Sculpture in Antiquity, Cultural Gate of the Aegean Archipelago, Athens 2007 (a detailed per period and per island arroyo).

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_sculpture

0 Response to "One Unique Feature of Hellenistic Art Was for a Sculptor to Carve Drapery and Folds in Clothing"

Post a Comment